Dr. Catherine Brinkley is an Associate Professor in Human Ecology, Community and Regional Development at the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences. With a PhD in city and regional planning, a veterinary medical degree, and a masters in virology, her research focuses on health equity and One Health, a concept that considers health shared between humans, animals and the environment. She is a former Fulbright Scholar, Watson Fellow, and National Science Foundation Career Award Winner.

She advances scholarship and practice on local governance, food systems, and sustainable development. Her work is used internationally by the United National Food Agriculture Organization as well as local communities to guide plans. Dr. Brinkley’s CV / GoogleScholar

Why I Do What I Do: Connecting People, Animals, and the Environment Through Land-Use Planning

When I tell people my work focuses on improving health for humans, animals, and the environment—mostly through land-use planning—I sometimes get blank stares. After all, "urban planner" or "academic" isn't exactly on the dream job list for most kids. So how did I end up here?

Finding My Path: A Journey Across Lands and Lessons

Since I was little, I’ve felt this pull—a calling to protect wildlife and conserve the spaces we all depend on. Maybe it came from those long hikes along the Appalachian Trail with friends. Or perhaps it was swimming under the aurora borealis in Lake Superior, where nature felt both vast and intimate. It could have been fishing with my grandpa in the Gulf of Mexico, where we talked about tides and local politics.

Growing up, my family moved every two years because my dad worked in the military. Constantly relocating gave me a front-row seat to the incredible diversity of places, cultures, and ecosystems across the U.S. and beyond. Yet, no matter where we lived, my goal remained steady: I wanted to help wildlife and protect habitats. For most of my childhood, that meant becoming a veterinarian.

Undergraduate Discoveries: Expanding My Vision

I dove headfirst into this ambition at Wellesley College, where I majored in biology and absorbed everything I could about ecosystems and conservation. But the turning point came when I stepped out of the classroom and into the world. Two study-abroad programs completely changed the way I saw conservation—and my future.

First, I traveled to Lake Baikal in Siberia, the oldest and deepest freshwater lake on Earth. There, I worked with conservationists and saw firsthand how protecting a place as vast and complex as Lake Baikal required collaboration—not just among scientists, but with governments and grassroots activists, too. Science alone wasn’t enough.

I also studied coral reefs in Belize and Costa Rica, two of the most biodiverse places on the planet. Immersing myself in these vibrant underwater worlds taught me that diversity—of species, perspectives, and strategies—is the key to resilience. Protecting nature meant understanding how systems work together, just like a reef relies on the interplay of tides, coral, fish, algae, and even humans to thrive.

These experiences opened my eyes to something bigger: conservation wasn’t just about biology. It was about people, places, and policies working in harmony.

Falling in Love with Design and Storytelling

Before committing to veterinary school, I decided to explore other ways I might contribute to conservation. I earned a Watson Fellowship, which let me spend a year traveling the world to study something I was fascinated by: zoo design.

I’d always wondered: how do zoos tell the story of conservation? How do their exhibits inspire children (and adults) to care about the natural world? My travels took me to countries across the globe, where I worked with architects, conservationists, and educators to answer these questions.

One highlight of the journey was partnering with the Jane Goodall Institute and architect Stephen Protz to design a new orangutan exhibit for the Shanghai Zoo. It wasn’t just about creating a space for animals—it was about teaching visitors how interconnected we all are and sparking a sense of responsibility for the planet.

These experiences helped me see conservation from yet another angle: how design and storytelling can shape public perception and inspire action. By the time I finished the fellowship, I realized my vision for the future needed to go beyond veterinary medicine. Conservation wasn’t limited to caring for individual animals or even herds—it needed people who understood how to shape the spaces and systems where animals, humans, and the environment coexist.

Bringing Science and Policy Together: From Lab to Land

A Fulbright Fellowship brought me back into the world of laboratory sciences where I documented how habitat fragmentation can give rise to something both fascinating and deeply concerning: deadly new diseases that jump from animals to humans. Later, when I joined the VMD-PhD program at the University of Pennsylvania, I worked with epidemiologist Dustin Brisson to model how novel diseases are amplified when multiple species are stressed with environmental changes. We described multiple cases where breaking up ecosystems—through urbanization, deforestation, or agriculture—created the perfect conditions for diseases to jump between species and spread more easily. Our work explained that when multiple species are stressed by their surroundings, it doesn’t just impact individual populations—it can create ripple effects that destabilize entire ecosystems and human health.

This research sparked something in me. I wanted these insights to be translated into real-world solutions. That’s why I founded the first veterinary student chapter for One Health, a global initiative that connects human, animal, and environmental health. But even that wasn’t enough. I realized I needed to expand my perspective beyond veterinary medicine if I wanted to make meaningful change. That’s when I set my sights on a PhD in land-use planning—a field where I could combine my science background with design and policy to create tangible action.

Delving into Planning Research

As a Planning PhD student, I had the incredible opportunity to collaborate with the United Nations on the World Livestock Report, where I examined how municipal codes regulate farm animals and wildlife in urban and agricultural areas. This work took me across the world and into archives, where I explored how local governments have historically managed the balance between nature, agriculture, and urban growth.

The project prompted a deeper dive into American history, where I reviewed hundreds of historic municipal codes. My goal was to understand a simple yet profound question: How did agriculture and urban areas work together? What I found was a hidden history of food system planning, revealing the intentional zoning and policy decisions that relegated farming to the outskirts of urban life.

As I researched, I became fascinated by peri-urban agriculture —the farms and green spaces that exist on the edges of cities. These areas serve as a critical bridge between urban and rural life, offering fresh food, green infrastructure, and biodiversity. Yet, they’re often overlooked in urban planning. It struck me as incredible that while urban areas occupy only 1-3% of the world’s land, food systems take up more than 50%—yet we rarely integrate agriculture into planning studies and discussions. This realization reinforced my mission: we need to rethink how we plan land, not just for cities, but for the ecosystems and food systems that sustain them.

Building a Better Food System: From Local to Global Connections

I quickly realized I wasn’t alone in these concerns when I conducted my first literature review of food systems research-- revealing a wealth of insights and unanswered questions about how to improve access, equity, and sustainability in the way we grow, distribute, and consume food. Then, in 2013, I had the incredible opportunity to work with Professor Eugenie Birch to organize the Feeding Cities: Food Security in a Rapidly Urbanizing World conference at the University of Pennsylvania. The event brought together 70 experts and over 450 attendees from across disciplines to tackle pressing questions about the future of food systems in our rapidly urbanizing world.

That conference set the stage for much of my research agenda, which I’ve since built around key areas like healthy food access, food deserts, community solutions to food deserts, cooperative grocery store interventions, urban farmers, street food vending, global food security, farm animal welfare, and restaurants. Each study offered a deeper understanding of how the complex food system works—or often fails—for people, animals, and the environment.

The Problem With Dividing Land

Reflecting on the lessons I learned during my study-abroad experiences, I began to notice patterns in the modern socio-ecological crises we face today. A significant issue, I realized, is the spatial and ideological divide between urban, agricultural, and wildlands. Urban sprawl often consumes prime farmland, forcing farms to move to marginal soils where achieving high yields requires more chemical inputs. This depletes ecosystems, erodes soil, and often lowers the quality of the food that must now be processed and shipped over long distances to urban consumers—many of whom are disconnected spatially and socially from the food systems that sustain them.

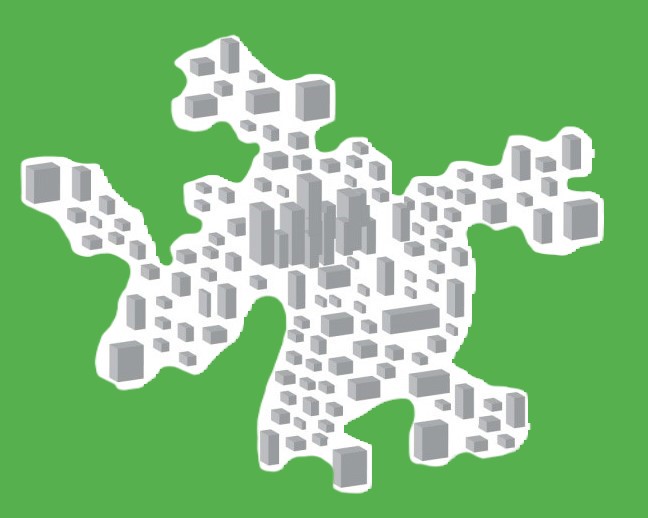

Paradoxically, my research showed that people valued living near working lands like farms and forests. In fact, they often pay a premium to live in these areas. More surprisingly, places that interweave agricultural lands with urban spaces tend to be the most desirable places to live. This insight inspired a new theory for urban development, one I call high-rugosity planning.

Cities as Coral Reefs: High-Rugosity Planning

Think of a coral reef. Its highly irregular, textured surface supports diverse forms of life by creating many niches. Cities could be like coral reefs, fostering a dynamic interface between developed and undeveloped lands. By increasing the urban-non-urban interface, we can blend spaces in a way that supports biodiversity, environmental health, and human well-being.

With Dr. Subhashni Raj, I helped quantify just how rugose urban areas already are—despite historical attempts to keep development neat and concentric. This work has sparked new ideas about how we can design cities to look and function more like coral reefs, integrating diverse land uses rather than isolating them. I am grateful to one of the top-cited planning schoolars, Professor Reid Ewing for featuring my research in his 2019 “Research You Can Use” column for the American Planning Association.

Connecting the Dots in Agroecological Systems

In design, there is an adage that form follows function. Spatial research was not enough, I needed to understand the connections between various land-uses. This approach led me to international collaborations with colleagues studying agroecological food systems in a city-region context. We examined how local decisions—such as paving over a farm in one city—can spur land conversion far away, often on the other side of the country or even the world. Documenting these connections allowed us to better understand how food systems grow and adapt over time, with significant implications for addressing hunger, supporting new food businesses, and improving global food security.

With many incredible students in our Equity, Land, and Food Systems (ELFS) lab, we built one of the largest databases of local food systems, and we used this research to address how to integrate and strengthen Food, Energy, and Water (FEW) systems across urban and rural lands.

From Food to Energy: Lessons in Localization

It’s not just food systems that have globalized over the last two centuries—our energy systems have, too, with profound consequences for climate change. Interestingly, my research has shown that when energy systems are relocalized, nations can simultaneously reduce greenhouse gas emissions and increase profits. A great example comes from Sweden’s district energy projects and campus energy relocalization efforts, where communities successfully reduced their carbon footprint while creating economic value.

Our research has shown that, much like farms, well-designed energy projects can also boost property values in nearby communities. Whether it’s a solar farm, wind turbines, or district heating infrastructure, thoughtful planning ensures that people see these systems as an asset, not an intrusion.

Planning for Environmental Justice

Ultimately, these decisions about what we want close to us and what we want to push away boil down to planning—and planning often reflects power dynamics. Historically, Locally Unwanted Land Uses (LULUs), like industrial plants or landfills, have been disproportionately placed in lower-income or marginalized communities. These same communities often lack access to healthy food, clean water, and renewable energy, compounding the cycle of environmental injustice.

Ensuring healthy food access, safe drinking water, and clean energy is part of addressing legacy and future FEW planning. I work in a state that has mandated that local jurisdictions address EJ. To help spur this effort forward, I partnered with the California Environmental Justice Alliance and several state agencies, including the Governor’s Office of Land-use and Climate Initiatives and the California Air Resources Board.

We developed a searchable database of plans, now called PlanSearch. California is the only state to have such planning data infrastructure, making it easier to evaluate plans and draft more impactful plans. Thus far, we have evaluated how California cities and counties plan for housing, climate, densification, and EJ –all while making it easier for students, the public, and researchers to rapidly assess plan contents, celebrate and improve on existing efforts. Partnering with the Berkeley Othering and Belonging Institute, I also led a team with Dr. Clancy McConnell to build the California Zoning Atlas—helping to visualize zoning codes across the state as part of the National Zoning Atlas Project under Dr. Sara Bronin at Cornell University.

What’s Next? Planning for the Future

My current research focuses on improving planning practices by leveraging data and machine learning to speed up how we read, draft, and evaluate plans. If you are a student who wants to work on this topic—please reach out to our lab to learn about research opportunities.

At the same time, I’m fascinated by the history of planning—especially how past governance decisions for food, energy, and water (FEW) systems have shaped today’s challenges. This exploration forms the foundation of my first book project.

Outside of my academic work, I love volunteering for issues related to social equity, outdoor programs for kids, and animal rehabilitation. These passions reflect the same drive that brought me here: a commitment to building systems that support humans, animals, and the environment.